by Ramon Jiménez

It is well-known that the first references in print that seemed to connect William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon to the playwright William Shakespeare appeared in the first collection of his plays — the First Folio, seven years after his death. On the other hand, we can identify at least ten people who personally knew the William Shakespeare of this Warwickshire town, or met his daughter, Susanna. At least six of them, and possibly all of them, were aware of plays and poems published under the name of one of the country’s leading playwrights, William Shakespeare. All ten left us published books, poems, letters, notebooks, or diaries, some of which referred directly to events or people in Stratford. Yet none of these nine men and one woman — it is fair to call them eyewitnesses — left any hint that they connected the playwright with the person of the same name in Stratford-upon-Avon.

William Camden

William Camden was the most eminent historian and antiquary of the Elizabethan age, and was deeply involved in the literary and intellectual world of his time. He knew Philip Sidney, was a valued friend of Michael Drayton, and is said to have been a teacher of Ben Jonson. His most famous work was Britannia, a history of England first published in Latin in 1586. It was translated, and frequently reprinted, and he revised it several times before his death in 1623.

Another of Camden’s books was Remaines Concerning Britain, a series of essays on English history, English names and the English language that he published in 1605. Camden wrote poetry himself, and in the section on poetry, he referred to poets as “God’s own creatures.” He listed eleven English poets and playwrights who he thought would be admired by future generations — in other words, the best writers of his time (Remaines 287, 294). Among the eleven were six playwrights, including Jonson, Chapman, Drayton, Daniel, Marston, and William Shakespeare.

Two years later, in 1607, Camden published the sixth edition of his Britannia, which by then had doubled in size because of his extensive revisions and additions. He arranged the book by shire or county, with his description of each beginning in the pre-Roman period and extending to contemporary people and events. With Camden’s interests and previous work in mind, it is surprising to find that in this 1607 edition, and in his subsequent editions, in the section on Stratford-upon-Avon, he described this “small market-town” as owing “all its consequence to two natives of it. They are John de Stratford, later Archbishop of Canterbury, who built the church, and Hugh Clopton, later mayor of London, who built the Clopton bridge across the Avon”(Britannia 2:445). In the same paragraph, Camden called attention to George Carew, Baron Clopton, who lived nearby and was active in the town’s affairs.

There is no mention of the well-known poet and playwright, William Shakespeare, who had been born and raised in Stratford-upon-Avon, whose family still lived there, and who by this date had returned there to live in one of the grandest houses in town. Elsewhere in Britannia, Camden noted that the poet Philip Sidney had a home in Kent. We know he was familiar with literary and theatrical affairs because he was a friend of the poet and playwright Michael Drayton (Newdigate 95), and he noted in his diary the deaths of the actor Richard Burbage and the poet and playwright Samuel Daniel in 1619.[1] He made no such note on the death of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon in April 1616.

It might be suggested that Camden was unfamiliar with the Warwickshire area, and wasn’t aware that one of the leading playwrights of the day lived in Stratford-on-Avon. But could this be true? In 1597 Queen Elizabeth had appointed Camden to the post of Clarenceaux King of Arms, one of the two officials in the College of Arms who approved applications for coats of arms. Two years later, John Shakespeare, William’s father, applied to the College to have his existing coat of arms impaled, or joined, with the arms of his wife’s family, the Ardens of Wilmcote (Chambers 2:18–32). Some writers have asserted that William Shakespeare himself made this application for his father, but there is no evidence of that. What is likely is that William paid the substantial fee that accompanied the application.

The record shows that Camden and his colleague William Dethick approved the modification that John Shakespeare sought. However, in 1602 another official in the College brought a complaint against Camden and Dethick that they had granted coats of arms improperly to twenty-three men, one of whom was John Shakespeare. Camden and Dethick defended their actions, but there is no record of the outcome of the matter, and the Shakespeare coat of arms, minus the Arden impalement, later appeared on the monument in Holy Trinity Church. Because of this unusual complaint Camden had good reason to remember John Shakespeare’s application, and it is very probable that he had met both father and son. At the least, he knew who they were and where they lived.

William Camden had another occasion to come in contact with the Shakespeares. In the summer of 1600, when the famous Sir Thomas Lucy died, Camden bore Lucy’s coat of arms in the procession and conducted the funeral at Charlecote, only a few miles from Stratford-upon- Avon (Malone 2:556). Thomas Lucy knew the Shakespeares also. When he was justice of the peace in Stratford-upon-Avon, John Shakespeare was brought up before him more than once. John may even have attended Lucy’s funeral, but it seems likely that William was too busy to go. During 1600, seven or eight of William Shakespeare’s plays were printed for the first time and, according to most orthodox scholars, in the summer of 1600 he was hurrying to finish up Hamlet.

So, even though William Camden revered poets, had several poet friends, and wrote poetry himself, even though he knew the Shakespeares, father and son, and even though he mentioned playwrights and poets in his books and in his diary, he never connected the Shakespeare he knew in Stratford-upon-Avon with the one on his list of the best English poets.

Michael Drayton

Another eyewitness is the poet and dramatist Michael Drayton, who was born and raised in Warwickshire, only about twenty-five miles from Stratford-upon-Avon. It is hard to imagine that Michael Drayton was unaware of Shakespeare. The two were almost exact contemporaries. They both wrote sonnets, and many critics have even found the influence of Shakespeare in Drayton’s poetry (Campbell 190–91). Also, they both wrote plays that appeared about the same time on the London stage in the late 1590s. In fact, in 1599 Drayton, along with Anthony Munday, Robert Wilson, and Richard Hathaway, wrote a play — Sir John Oldcastle — that was supposed to be a response to Shakespeare’s plays about Falstaff (Chambers 1:134).

In 1612 Drayton published the first part of Poly-Olbion, a poetical description of England, and a county-by-county history that included well-known men of every kind. In it were many references to Chaucer, to Spenser, and to other English poets. But in his section on Warwickshire, Drayton never mentioned Stratford-upon-Avon or Shakespeare, even though by 1612 Shakespeare was a well-known playwright. It seems that Drayton never connected the writer to the William Shakespeare he must have known in Stratford-upon-Avon.

How do we know he knew him? Many supporters of the Stratford theory think so. Samuel Schoenbaum wrote that it is “not implausible” that Drayton and Shakespeare, and Ben Jonson as well, had that “merry meeting” reported in the 1660s by John Ward, the vicar of Stratford- upon-Avon (Schoenbaum 296). In fact, more than one scholar has found evidence that Michael Drayton was the “Rival Poet” of the sonnets. But we have better evidence than that.

Drayton’s life is well-documented. He had a connection to the wealthy Rainsford family, who lived at Clifford Chambers, a couple of miles from Stratford-upon-Avon. Drayton had been in love with Lady Rainsford from the time she was Ann Goodere, a girl in the household in which he was in service in the 1580s. She was the subject of his series of love sonnets, Ideas Mirrour, published in 1594. Although she rejected him and married Henry Rainsford in 1595, Drayton hung around their household and made himself a friend of the family. He apparently never stopped loving her, and from the early 1600s until his death in 1631 he made frequent visits to their home at Clifford Chambers, sometimes staying all summer.

The Shakespearean scholar Charlotte Stopes was certain that Shakespeare would have been “an honored guest” at the Rainsford home because of the family’s literary interests, but there is no record of such a visit (Stopes 1907, 206). But even if Shakespeare may never have visited the Rainsfords, Dr. John Hall, the man who married his daughter, certainly did. Hall was the Rainsfords family doctor and once treated Drayton for a fever, probably at the Rainsford home. The doctor made a record of it in his case book, and even noted that Drayton was an excellent poet (Lane 40–41). His treatment for Drayton’s fever was a spoonful of “syrup of violets,” but he did recover.

Another reason that Drayton must have been aware of a playwright named Shakespeare was that in 1619 Sir John Oldcastle, the play Drayton had written with three others, was printed by William Jaggard and Thomas Pavier with Shakespeare’s name on the title page (Chambers 1:533–34). This is certainly something an author would notice.

It is very probable that if Drayton thought that Dr. Hall’s father-in-law was the famous playwright and poet, he would have written or told someone about him. But there is no mention of Shakespeare anywhere in his substantial correspondence. In all his writings — the collected edition is in five volumes — despite his mention of more than a dozen contemporary poets and playwrights, Drayton never referred to William Shakespeare at all until more than ten years after Shakespeare’s death. When he finally did, he wrote four lines about what a good comedian he was. It is unclear whether he was referring to him as a playwright, an actor, or in some other capacity.

Thomas Greene

Our third eyewitness connects Michael Drayton and William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon even more closely. In the 1603 edition of one of Drayton’s major poems, The Barons’ Wars, there appeared a commendatory sonnet — a Shakespearean sonnet — by one Thomas Greene.[2] Also in 1603, the bookseller and printer William Leake published a poem by this same Thomas Greene titled “A Poet’s Vision and a Princes Glorie.” In seventeen pages of forgettable verse, Greene predicted a renaissance of poetry under the new King, James I. (For more than twenty years, beginning in 1596, William Leake was the holder of the publishing rights to Venus and Adonis [Chambers 1:544].)

Orthodox scholars agree that this Thomas Greene was none other than the London solicitor for the Stratford Corporation, and the Town Clerk of Stratford-upon-Avon for more than ten years (Dobson & Wells 173). He had such a close relationship with the Shakespeares that he named two of his children William and Anne. He and his wife and children lived in the Shakespeare household at New Place for many months during 1609 and 1610 (Schoenbaum 282). He was also the only Stratfordian contemporary of Shakespeare to mention him in his diary. This was in connection with the Welcombe land enclosure matter, where he referred to him as “my cosen Shakspeare” (Campbell 272).

Thomas Greene was also a friend of the dramatist John Marston, and they were both resident students at the Middle Temple during the mid-1590s. Yet nowhere in his diary or in his letters that have survived, does Thomas Greene — apparently the author of a Shakespearean sonnet himself — even hint that the Shakespeare he knew was a poet. What a shame that Greene made no comment in his diary about a book called SHAKE-SPEARE’S SONNETS, with its strange dedication to “our ever-living poet,” that was published in London in 1609, about the time he was living in the Shakespeare household. Nor does he mention in his diary the death of the supposedly famous playwright in the spring of 1616. Mrs. Stopes wrote, “It has always been a matter of surprise to me that Thomas Greene, who mentioned the death of Mr. Barber, did not mention the death of Shakespeare.” For this she offered the astounding explanation, “Perhaps there was no need for him to make a memorandum of an event so important to the town and himself” (Stopes 1907, 89). Thomas Greene’s failure to make any note of his friend’s dramatic genius is especially unusual because he knew him so well, and he was a published poet himself.

John Hall

Our fourth eyewitness is that same Dr. John Hall who came to Stratford-upon-Avon from Bedfordshire in the early 1600s, and married Susanna Shakespeare in 1607. During his more than thirty years of practice in Warwickshire, Dr. Hall was considered one of the best physicians in the county, and was called often to the homes of noblemen throughout the area. As a leading citizen of the town, he was elected a Burgess to the City Council three times before he finally accepted the office. On the death of his father-in-law in 1616, Dr. Hall, his wife Susanna, and their eight-year-old daughter Elizabeth moved into New Place with William Shakespeare’s widow Anne.

A few years after Dr. Hall’s death in 1635, it transpired that he had kept hundreds of anecdotal records about his patients and their ailments — records that have excited the curiosity of both literary and medical scholars. Two notebooks were recovered, and one containing about 170 cases was translated from the Latin and published by one of his fellow physicians. The other, possibly once in the possession of the Shakespearean scholar Edmond Malone, has, unfortunately, disappeared. In the single surviving manuscript are descriptions of dozens of Dr. Hall’s patients and their illnesses, including his wife Susanna, and their daughter Elizabeth. Also mentioned are the Vicar of Stratford-upon-Avon and various noblemen and their families, including Michael Drayton’s friends the Rainsfords, and of course Drayton himself. In his notes about one patient Thomas Holyoak, Dr. Hall mentioned that his father Francis Holyoak had compiled a Latin-English dictionary. John Trapp, a minister and the schoolmaster of the Stratford Grammar School, he described as being noted “for his remarkable piety and learning, second to none” (Joseph 47, 94).

But nowhere in the notebook that has survived is there any mention of Hall’s father-in-law William Shakespeare. This, of course, has vexed and puzzled scholars. Dr. Hall surely treated his wife’s father during the ten years they lived within minutes of each other. Why wouldn’t he record any treatment of William Shakespeare and mention his literary achievements as he had Michael Drayton’s and Francis Holyoake’s? The accepted explanation has always been that of the few cases in Dr. Hall’s notebook that he dated, none bears a date earlier than 1617, the year after Shakespeare’s death. For decades scholars have assumed that any mention of Shakespeare was probably in the lost notebook.

But recently this assumption proved false when a scholar found that at least four, and as many as eight, of the cases Hall recorded can be dated before Shakespeare died, even though the doctor didn’t supply the dates himself. Because Dr. Hall nearly always noted the age and residence of his patients, most of them have been identified and their birth dates found in other sources. The earliest case in the existing manuscript can be dated in 1611, others in 1613, 1614 and 1615, and another four in 1616, the very year of Shakespeare’s death (Lane 351).

It appears that Dr. Hall made his notes shortly after treating his patients, but didn’t prepare them for publication until near the end of his life. Hall was obviously aware and admiring of his patients’ status and achievements, especially their scholarly and literary achievements, as his comments about Drayton, Holyoake, and others reveal. By 1630 William Shakespeare was well-known as an outstanding, if mysterious, playwright. The Second Folio was published in 1632, and many of his plays were issued in quarto, as well as several printed tributes. Thus, there is good reason to expect that Dr. John Hall would have noted his treatment of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon during the ten years he knew him — if he thought he were someone worthy of mention. It is indeed strange that in the early 1630s, as he was collecting the cases he wished to publish, he should neglect to include any record of his treating his supposedly famous father-in-law. Mrs. Stopes called it “the one great failure of his life” (Stopes 1901, 82).

James Cooke

Our fifth eyewitness is Dr. James Cooke, a surgeon from Warwick who was responsible for the publication of John Hall’s casebook. Although he was about twenty years younger than Hall, Cooke was acquainted with him from the time they had both attended the Earl of Warwick and his family. In the 1640s a Parliamentary army was contending with the army of Charles I in a civil war that would end with Charles’s defeat and eventual beheading in 1649. Both royalists and rebels occupied Stratford-upon-Avon on different occasions. In 1644 Dr. Cooke was attached to a Parliamentary army unit assigned to guard the famous Clopton Bridge over the Avon at Stratford-upon-Avon. At this date Dr. John Hall had been dead nine years and, according to Cooke, he and a friend decided to visit Hall’s widow Susanna “to see the books left by Mr. Hall” (Joseph 105).

When they arrived at New Place and met Susanna, Cooke asked if her husband had left any books or papers that he might see. When she brought them out, Cooke noticed two manuscript notebooks handwritten in a Latin script that he recognized as Dr. Hall’s. Susanna was confident that it wasn’t her husband’s handwriting, but when Dr. Cooke insisted, she agreed to sell him the manuscripts, and he carried them away with great satisfaction.

He eventually translated one of the notebooks, added some cases of his own, and published it in 1657 under a very long title that is commonly shortened to Select Observations on English Bodies. On the title page John Hall is described as a “Physician, living at Stratford upon Avon, in Warwickshire, where he was very famous” (Joseph 104). In his introduction to the book, Cooke described his visit with Susanna, during which neither of them referred to her supposedly famous father, nor to any books or manuscripts that might have belonged to him. In fact, from Dr. Cooke’s report of the meeting, neither Shakespeare’s daughter Susanna nor the doctor himself was aware of any literary activity by the William Shakespeare who had lived in the very house they were standing in.

As is well known, William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon mentioned no books, papers, or manuscripts in his will. After certain specific bequests, he left the rest of his goods and “household stuffe” to his daughter and her husband, John Hall. In contrast, Dr. Hall referred in his will to “my study of books” and “my manuscripts,” and left them to his own son-in-law Thomas Nash (Lane 350).

Sir Fulke Greville

A sixth eyewitness is Sir Fulke Greville, later Lord Brooke, whose family had lived near Stratford for more than two hundred years, and who must have known the Shakespeare family. He was born in 1554 at Beauchamp Court, less than ten miles from Stratford-upon-Avon, in the vicinity of Snitterfield, the home of Richard Shakespeare, grandfather of William. He was related to the Ardens, the family of Shakespeare’s mother, and displayed the arms of the Arden family on his own coat-of-arms (Adams 451).

Greville was a man of importance in Warwickshire. In 1592 he, Sir Thomas Lucy, and five others were appointed to a Commission to report on those who refused to attend church. In September of that year, the Commission reported to the Privy Council that nine men in the parish of Stratford-upon-Avon had not attended church at least once a month. Among the nine was John Shakespeare, father of William (M. Eccles 33). Throughout his life Greville sought preferment at court, and eventually became Chancellor of the Exchequer and Treasurer of the Navy. On the death of his father in 1606, Greville was appointed to the office his father had held — Recorder of Warwick and Stratford-upon-Avon, and remained in it until his death in 1628. In this position he could hardly have been unaware of the Shakespeare family.

Greville was also a serious poet and dramatist. During the late 1570s he composed a cycle of 109 poems, 41 of which were sonnets, and two decades later wrote three history plays. But he was one of those noblemen who disdained appearance in print, and in fact refused to allow any publication of his work while he was alive. The only work of his that appeared during his lifetime was an unauthorized printing of his play Mustapha in 1609. This was the same year that SHAKE-SPEARE’S SONNETS were published — probably without the permission of its author, supposedly his neighbor down the road.

Greville preferred the company of poets and philosophers, and his closest friends were the poets Edward Dyer and Philip Sidney. Greville was also acquainted with John Florio, Edmund Spenser, and Ben Jonson. Another poet and playwright William Davenant, who claimed to be a godson, or maybe a son, of William Shakespeare, entered Greville’s household as a page when he was eighteen (DNB). Greville corresponded with the poet and playwright George Chapman (Crundell 137), who was mentioned by Francis Meres in 1598, along with William Shakespeare, as one of the best English playwrights. Greville was a patron of Samuel Daniel, the poet and playwright from nearby Somerset who dedicated “Musophilus,” probably his finest poem, to him in 1599. Both Chapman and Daniel were about the same age and from the same class as William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon.

Greville’s plays have never been performed, and he is best known today for his biography of Philip Sidney, in which he wrote about both himself and Sidney, and their twenty-year friendship. A number of letters both to and from Greville have survived. Yet nowhere in any of Greville’s reminiscences, or in the letters he wrote or received, is there any mention of the well-known poet and playwright, William Shakespeare, who supposedly lived a few miles away.[3] Charlotte Stopes wrote: “It is always considered strange that such a man should not have mentioned Shakespeare” (1907, 171). Greville has been described as “one of the leaders of the movement for the introduction of Renaissance Culture into England” (Whitfield 366). Yet so far as we know, Greville never made any connection between the resident of the nearby town and the dramatist who bore the identical name and who, more than any other, used Renaissance literary sources for his plays — William Shakespeare.

Edward Pudsey

Another eyewitness who must have known William Shakespeare of Stratford was an obscure theatre-goer named Edward Pudsey who was perhaps only the second individual we know of to write out passages from a Shakespeare play. Very little is known about Edward Pudsey, except that he was born in Derbyshire in 1573 and died in 1613 at Tewkesbury, about 25 miles from Stratford (DNB). There is a 1591 record of a Pudsey family living at Langley, about five miles from Stratford, and only three miles from Park Hall, the home of the Ardens, parents of Shakespeare’s mother Mary (Savage vi) .

In 1888 scholars were fortunate to discover a 90-page manuscript that was inscribed “Edward Pudsey’s Book.” In it Pudsey had copied passages from several literary works in the fields of history, philosophy and current events — as well as from contemporary plays. The dates entered in the manuscript range from 1600 to 1612, the year before Pudsey died. Besides passages from Machiavelli, Thomas More, Francis Bacon, and others, Pudsey carefully transcribed selections from 22 contemporary plays — four by Ben Jonson, three by Marston, seven by Dekker, Lyly, Nashe, Chapman, and Heywood. And eight by William Shakespeare.

The extracts from Hamlet and Othello are especially interesting because of their variations from the printed versions. The quotation from Hamlet is slightly different from the 1604 Quarto and the 1623 Folio. The quotation from Othello contains lines that do not appear in the Quarto, which was not published until 1622. After the Othello quotation, Pudsey wrote the letters “sh,” a reasonably clear indication that he knew that the play was by William Shakespeare. The English scholar who examined the manuscript asserted that the quotations from Othello and Hamlet were written in a section that she dated no later than 1600 (Rees 331). Thus, it is probable that Edward Pudsey had access to now-lost quartos of Othello and Hamlet, or had seen the plays and written down the dialogue in 1600 or earlier.

But nowhere in the hundreds of entries in Edward Pudsey’s Book is there any indication that he was aware that the playwright whose words he copied so carefully lived in nearby Stratford- upon-Avon.

Queen Henrietta Maria

Our eighth eyewitness is Henrietta Maria, the 15-year-old daughter of King Henry IV of France and Marie de Médicis, who, by arrangement, became the wife and Queen of Charles I soon after his coronation as King of England in 1625. The new American colony of Maryland, founded in 1632, was given its name in honor of Henrietta Maria.

Both Charles and Queen Henrietta were theatre buffs and enthusiastic patrons of the drama. King Charles even collaborated on a play with James Shirley in the 1630s, and was so fond of Shakespeare that he kept a copy of the Second Folio by his bedside. In this copy are found the alternative titles he assigned to several of the plays, such as “Pyramus and Thisbe” for A Midsummer Night’s Dream and “Malvolio” for Twelfth Night (Birrell 45). To the Puritans, who executed Charles in 1649, his dissolute character was exemplified by his love of plays. One Puritan pamphlet asserted that he would have succeeded as king “had he studied scripture half so much as he did Ben Jonson or Shakespeare” (Campbell 107).

Queen Henrietta was also an amateur playwright, and even more enamored of the stage than her husband. She was the first English monarch to attend a performance in a public playhouse, and enjoyed performing the leading roles in her own masques at Court — behavior that shocked the English public (Campbell 312). According to Michael Dobson and Stanley Wells, the word “actress” was first used in reference to her (187). In her 1632 masque Tempe Restored, professional women singers took the stage for the first time in England. Joining her on the stage on many occasions were several of her ladies-in-waiting, including Beatrice, the Countess of Oxford, wife of the 19th Earl, Sir Robert de Vere.

In 1642 Charles and his Parliament reached an impasse over taxes, and when he attempted to arrest five members, Parliament was moved to authorize an army, and a Civil War broke out. The Queen was in Holland at the time, but she quickly began rounding up support for the Royalist army. Early the next year she landed in Yorkshire with a large supply of ammunition she had solicited on the continent. From there she journeyed south to relieve her husband who was in the field with his army near Oxford. Traveling on horseback, the “Generalissima,” as she called herself, reached Warwickshire in early July 1643, and on July 11 arrived in Stratford-upon-Avon at the head of an army of three thousand foot, thirty companies of horse and dragoons, six pieces of artillery, and 150 wagons (Plowden 186).

The records of the Stratford Corporation document the visit of Queen Henrietta Maria and the substantial expense it incurred to provide a banquet for her (Fox 24). Although specific records of it are lacking, scholars accept a tradition that the Queen stayed two nights at New Place, then the home of William Shakespeare’s daughter Susanna, her daughter Elizabeth, and son-in-law Thomas Nash (Lee 509; Schoenbaum 305).

Queen Henrietta was an exceptional letter-writer. Hundreds of her letters to her husband, her nephew Prince Rupert, and others have been collected and printed. But none of the letters she wrote before or after her visit to Stratford-upon-Avon contains any mention of her stay at New Place, or any indication that she had met the daughter and granddaughter of the famous playwright whom she emulated and whom her husband venerated.

What could be the explanation for this? By 1643 there had been several visitors to the Holy Trinity Church, where the statue of William Shakespeare had been installed more than twenty years earlier (Chambers 2:239, 242–43). But if Queen Henrietta walked over to the church to see the memorial to the famous playwright, she never wrote about it. One explanation might be that she knew that the Stratford Shakespeare was a myth. A decade earlier she had been closely associated with Beatrice, the Countess of Oxford, and her husband, Robert de Vere, the 19th Earl. She also knew Ben Jonson, the artificer of the First Folio, who was still writing masques for the Court in the 1630s. Any one of the three might have told her about the aristocrat who concealed his writings by adopting a commoner’s name as his pseudonym. Any one of them might have told her that she would find nothing about the playwright Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Further evidence suggests that plays and playwrights were not welcome in Stratford-upon-Avon. It is well known that during the thirty years between 1568 and 1597 numerous playing companies visited and performed there. But by the end of this period the Puritan officeholders in the town finally attained their objective of banning all performances of plays and interludes. In 1602 the Corporation of Stratford ordered that a fine of ten shillings be imposed on any official who gave permission for any type of play to be performed in any city building, or any inn or house in the borough. This in a year that five or six plays by Shakespeare, their alleged townsman, were being performed in London.[4]

In 1612, just four years before their neighbor’s death, this fine was increased to ten pounds. In 1622, when work on the great First Folio was in progress, the Stratford Corporation paid the King’s Players the sum of six shillings not to play in the Town Hall (Fox 143–44). Surely by 1622, some thirty years after his name had first appeared in print, the people of Stratford would have been aware that one of England’s greatest poets and playwrights had been born, raised, and then retired in their own town. That is, if such a thing were actually true.

Philip Henslowe

Our ninth eyewitness was a London businessman who decided to build a playhouse, and then became a successful theatrical entrepreneur. Philip Henslowe and his partner had operated the Rose Theatre for about four years before he began, in 1592, making entries in an old notebook about his theater and the companies that played in it, primarily the Admiral’s Men (Foakes xv). The surviving 242-page manuscript, now called “Henslowe’s Diary,” is a goldmine of references to plays, playhouses, and playing companies in London, and mentions the name of just about everybody who was anybody in the Elizabethan theatre in the 1590s.

Although Henslowe kept his Diary on and off for less than ten years, we can find in it, or in other Henslowe manuscripts, the names of 280 different plays, about 240 of which have entirely disappeared. The names of fully 170 of these plays would be totally unknown today, except for their mention in Henslowe’s Diary (Bentley 15). The Diary contains reports of performances at the Rose Theatre by all the major playing companies of the time. There are also dozens of actors named, and no less than 27 playwrights.

In his Diary, Henslowe kept records of the loans he made to playwrights, and of the amounts he paid them for manuscripts. Among the playwrights mentioned are the familiar names of Chapman, Dekker, Drayton, Jonson, Marston, and Webster. There are also some unfamiliar names, such as William Bird, Robert Daborne, and Wentworth Smith, the other “W.S.” But there is one familiar name that is missing. Nowhere in the list of dozens of actors and twenty-eight playwrights in Henslowe’s Diary do we find the name of William Shakespeare.

It might be objected that Henslowe also failed to mention several other familiar playwrights, such as Beaumont, Fletcher, Ford, Lyly, Kyd, Marlowe, Greene, and Peele. But there are good reasons for these omissions. Beaumont, Fletcher, and Ford didn’t begin writing plays until after the period of Henslowe’s Diary. Marlowe and Greene died within a year of the first entry in the Diary; Kyd died a year later, and Lyly and Peele wrote their last plays in 1593 and 1594.

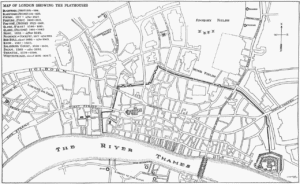

Admittedly, Shakespeare is supposed to have been an actor, playwright, and sharer in the Chamberlain’s Men company, which played in the Globe Theatre, the principal competitor of Henslowe’s Rose Theatre. But the Globe and the Rose theatres were situated very near each other, and Henslowe had to walk past the Globe every day on his way to work (C. Eccles 69). His Diary contains many transactions with actors and playwrights associated with the Chamberlain’s Men, and his entries for June 1594 record that the Chamberlain’s Men and the Admiral’s Men performed more than a dozen plays together at his Newington Butts theater about a mile away (Campbell 583). This is the period during which most scholars claim that William Shakespeare was acting with the Chamberlain’s Men.

If Shakespeare really were the busy actor and playwright we are told he was, then Henslowe would surely have known him, and mentioned him somewhere in his Diary. But although Henslowe mentioned several Shakespeare plays that were performed in his theatre, he never mentioned the name of the man who wrote them, and who had an attachment to a theatre exactly one hundred yards away.

Edward Alleyn

Our last eyewitness is Edward Alleyn, the most distinguished actor on the Elizabethan stage. He was also a musician, a book and playbook collector, a philanthropist, and a playwright (Wraight 211–19). He was born about two years after William Shakespeare and came from the same class. His father was an innkeeper, and Alleyn was still in his teens when he began acting on the stage. He was most famous for his roles in Marlowe’s plays, but he also must have acted in several of the Shakespeare plays performed at the Rose Theatre, such as Titus Andronicus and Henry VI (Carson 68). In 1592 he married Philip Henslowe’s step-daughter and entered the theatre business with his father-in-law.

Edward Alleyn also kept a diary that survives, along with many of his letters and papers. They reveal that he had a large circle of acquaintances throughout and beyond the theatre world that included aristocrats, clergymen, and businessmen, as well as men in his own profession, such as John Heminges, one of the alleged editors of the First Folio. In his two-volume edition of Edward Allen’s Memoirs (1841), John Payne Collier printed several references that Alleyn made to Shakespeare and to his plays, but they have all been judged forgeries (Chambers 2:386–90). The alleged reference by Alleyn to Shakespeare that has puzzled scholars the most is one that Collier claimed he found on the back of a letter written to Alleyn in June 1609. There, Alleyn supposedly recorded a list of purchases under the heading “Howshowld stuff” — at the end of which are the words “a book. Shaksper sonetts 5d.” Although this letter has been lost, the entry has been accepted as genuine by some scholars (Rollins (2:54 and Freeman 2:1142), but rejected as a forgery by others (Race 113 and Duncan-Jones 7). But forgery or genuine, it fails to suggest a connection with William Shakespeare of Stratford- upon-Avon.

Thus, except for this one questionable reference, nowhere in Alleyn’s diary or letters does the name William Shakespeare appear. It is impossible to believe that Edward Alleyn, who was at the center of the Elizabethan stage community for more than 35 years, would not have met the alleged actor and leading playwright William Shakespeare, and made some allusion to him in his letters or diary.

Conclusion

To sum up: We have the literary remains of ten different eyewitnesses, eight of whom must have come into contact with William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon — or should have if he were the actor and playwright we are told he was — and two who met his daughter Susanna. If two or three of these ten eyewitnesses had failed to associate the well-known playwright with the man bearing the same name in Stratford-upon-Avon, it would not be worth mentioning. But none of these ten, all of whom left extensive written records, apparently connected the man they knew, or the daughter of that man, with the well-known playwright.

We can be sure that if any one of these ten people had, just once, referred to William Shakespeare of Stratford as a playwright, or if his name had appeared in Henslowe’s Diary, just once, as being paid for a play, then those who reject the Stratford theory would have a lot of explaining to do. In fact, there is no record of anyone associating Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon with play-writing or any other kind of writing until the questionable front matter of the First Folio seven years after his death. Instead, the facts support the argument that the name Shakespeare was the pseudonym of a concealed author who did not write for money, did not sell his plays to playing companies or publishers, and was indifferent to their appearance in print.

Given the mystery of William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon, it is instructive to recall a similar instance of negative evidence in the well-known mystery story “Silver Blaze” by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In this story, Sherlock Holmes was called to a small town in Dartmoor where a racehorse had been stolen, and its trainer murdered. One of the clues that enabled Holmes to solve the case was his observation that at the time of the theft the dog guarding the stable failed to bark. In the usual run-up to the solution, the horse’s owner became impatient with Holmes, and asked him: “Is there any point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

Holmes replied: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.” The owner responded: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.” Holmes replied: “That is the curious incident.”

Holmes deduced that the silence of the dog meant the horse-thief was familiar to him, that there was nothing unusual about him — nothing to bark about. The silence of these ten eyewitnesses tells us the same thing. To them there was nothing about William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon that was worthy of note — nothing to bark about.

Endnotes

Camden’s Diary appeared in Camdeni Vitae, a life of Camden published in 1691 by Thomas Smith. The entries can be seen in the months of March and October under the year 1619.⇑

The text of the sonnet appears in v. 2 of Michael Drayton: Complete Works, J.W. Hebel, K. Tillotson & B.H. Newdigate, eds., Oxford: Blackwell, 1961.⇑

In Statesmen and Favourites of England Since the Reformation (1665), David Lloyd asserted that Greville wished to be “known to posterity” as “Shakespeare’s and Ben Johnson’s master.” But he cited no evidence to support the claim, and it is generally considered to be a fabrication. See Chambers v. 2, 250.⇑

Hamlet, Twelfth Night, The Merry Wives of Windsor, All’s Well that Ends Well, Richard III, Richard II.⇑

Works Cited

DNB = Dictionary of National Biography

Adams, Joseph Q. A Life of William Shakespeare. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1923.

Bentley, Gerald E. The Profession of Dramatist in Shakespeare’s Time, 1590–1642. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1986.

Birrell, T. A.: English Monarchs and Their Books: From Henry II to Charles II. London: British Library, 1986.

Camden, William. Remaines Concerning Britain (1605); Ed. R.D. Dunn. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1984

_____. Britannia (6th ed. 1607). Trans. Richard Gough. London: Printed for John Stockdale, 1806, v. 2, 445.

Campbell, Oscar & E. G. Quinn, eds. The Reader’s Encyclopedia of Shakespeare. New York: MJF Books, 1966.

Carson, Neil. A Companion to Henslowe’s Diary. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1988.

Chambers, E. K. William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems (2 vols.). Oxford: Oxford UP, 1930.

Crundell, H. W.: “George Chapman and the Grevilles.” Notes & Queries 185 (1943), 213.

Dobson, Michael & Stanley Wells. The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2001.

Drayton. See Hebel.

Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. London: Thomson Learning (Arden Shakespeare), 1998.

Eccles, Christine. The Rose Theatre. New York: Routledge (Theater Arts Books), 1990.

Eccles, Mark. Shakespeare in Warwickshire. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1963.

Foakes, R. A. ed. Henslowe’s Diary. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2d ed. 2002.

Fox, Levi. The Borough Town of Stratford-upon-Avon. Stratford-upon-Avon, UK, 1953.

Freeman, Arthur & Janet Ing Freeman. John Payne Collier: Scholarship and Forgery in the Nineteenth Century. 2004.

Hebel, J.W., K. Tillotson & B.H. Newdigate, eds. Michael Drayton: Complete Works. Oxford: Blackwell, 1961, v. 2.

Joseph, Harriet. Shakespeare’s Son-in-Law: John Hall, Man and Physician. Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1964.

Lane, Joan. John Hall and His Patients. Stratford-upon-Avon, UK: Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, 1996.

Lee, Sidney. A Life of William Shakespeare (14th ed.). New York: Dover, 1968.

Malone, Edmond. The Plays and Poems of William Shakespeare (Third Variorum Ed.). Ed. James Boswell. London: R.C. & J. Rivington, 1821, v. 2.

Newdigate, B.H. Michael Drayton and His Circle. London: Basil Blackwell & Mott, Corrected Edition, 1961.

Plowden, Alison. Henrietta Marie: Charles I’s Indomitable Queen. Stroud, UK: Sutton, 2001.

Race, Sydney. “J.P. Collier and the Dulwich Papers.” Notes & Queries 195 (1950), 112–14.

Rees, J. “Shakespeare and ‘Edward Pudsey’s Booke’: 1600.” Notes & Queries 237 (1992), 330–31.

Rollins, Hyder H., ed. A New Variorum Edition of Shakespeare: The Sonnets. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1944, v. 2.

Savage, Richard, ed. Shakespearean extracts from “Edward Pudsey’s Booke” temp. Q. Elizabeth & K. James I. London: Simpkin & Marshall, 1888.

Schoenbaum, Samuel. William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. New York: Oxford UP, 1977.

Stopes, Charlotte C. Shakespeare’s Warwickshire Contemporaries. Stratford-upon-Avon, UK: Shakespeare Head Press, 1907.

Shakespeare’s Family. London: Elliot Stock, 1901.

Whitfield, Christopher: “Some of Shakespeare’s Contemporaries in the Middle Temple — III.” Notes & Queries 211 (1966), 363–69.

Wraight, A.D. Christopher Marlowe and Edward Alleyn. London: Adam Hart, 1993.

Ramon Jiménez is the author of Shakespeare’s Apprenticeship: Identifying the Real Playwright’s Earliest Works (2018) (published by McFarland and also available on Amazon), a landmark study of several early Shakespeare plays and their revolutionary implications for the authorship question. He has also written two acclaimed histories of ancient Rome, both book club selections — Caesar Against the Celts (Da Capo, 1996) and Caesar Against Rome: The Great Roman Civil War (Praeger, 2000) — as well as several important articles including “The Case for Oxford Revisited” (2009), “Shakespeare by the Numbers: What Stylometrics Can and Cannot Tell Us” (2011), and “An Evening at the Cockpit: Further Evidence of an Early Date for Henry V” (2016), showing that Shakespeare’s Henry V was probably written and performed no later than 1584. In 2020, he published an important new article updating his work on Shakespeare’s early writings.

Ramon’s scholarly articles have appeared in The Oxfordian, the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, and in the anthology Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? (Shahan & Waugh eds. 2013). He and his wife, Joan Leon, are both former Trustees of the SOF and were jointly honored as Oxfordians of the Year in 2018. Ramon has also received the Award for Distinguished Shakespearean Scholarship at the Shakespeare Authorship Studies Conference at Concordia University in Portland, Oregon.

[Published on the SOF website Sept. 8, 2011, updated 2021. Originally published in two parts in the Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, v. 38, no. 4 (Fall 2002), p. 1, and v. 41, no. 1 (Winter 2005), p. 3; republished in Shahan & Waugh, Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? (2013), ch. 4, pp. 46–57.]