“Is That True?”

a book review by Warren Hope, Ph.D., written in memory of Charles Wisner Barrell, Craig Huston, Ruth Loyd Miller, and Bronson Feldman

a book review by Warren Hope, Ph.D., written in memory of Charles Wisner Barrell, Craig Huston, Ruth Loyd Miller, and Bronson Feldman

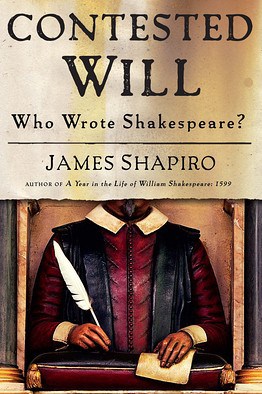

James Shapiro, Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? (2010). This review was published in Brief Chronicles, v. 2 (2010), p. 211 (PDF version here), and on April 20, 2010 (updated 2021), on the SOF website. Hope earned his Ph.D. in English from Temple University and has been an editor, publisher, and English instructor. He is a poet, has written several books, and is co-author with Kim Holston of The Shakespeare Controversy: An Analysis of the Authorship Theories (McFarland 1992, 2d ed. 2009).

This is the kind of argumentation one associates with political maneuvering rather than a serious quest for the truth on great issues and it makes one suspect that he is not very easy in his own mind about the case.

— J.Thomas Looney on the tactics of Professor Oscar Campbell

We are indebted to both James Shapiro and Alan Nelson for establishing a new phase in the history of the Shakespeare authorship question through the publication of two books — first Nelson’s Monstrous Adversary (2003) and now Shapiro’s Contested Will.

They are both grotesque books, reminiscent of gargoyles without the attractiveness. But they are grotesque for a reason. The authors treat evidence as if they were preparing show trials or cooking up disinformation for some nightmarish dictatorship. They are grotesque, not because they are demonic or dumb, but because they are expressions of the painful change that must take place if the study of Shakespeare is to be put on a rational footing.

This idea dawned on me when I caught myself thinking that Professors Shapiro and Nelson might be crypto-Oxfordians, determined to demonstrate to their colleagues that the price of continuing to maintain the Stratford cult is the utter abandonment of not only all scholarly standards but also common decency — and that the price is just too high to pay. But then I came to my senses. Although they do perform that function, they do so unintentionally and unconsciously — almost as if they are expressions of some Shakespeare authorship Zeitgeist, or hybrids thrown up by the reconciliation of opposites in the evolution of an idea.

Readers interested in a critique of Nelson’s pseudo-biography of Oxford should consult Peter Moore’s “Demonography 101” or the review essays by K.C. Ligon, Roger Stritmatter, or Richard Whalen. (Editorial Note: See “Nelson, Monstrous Adversary: Five Reviews.”) Those wanting a good traditional book review of Shapiro’s treatment of the authorship question can’t do better than by turning to William S. Niederkorn’s excellent review in the April 2010 issue of The Brooklyn Rail.

I’d like to do something different. I’d like to try and use some thoughts on Shapiro’s treatment of Looney and the Oxford case as a way to get at some larger issues.

When I recently listened to some legal scholars talk on TV about the legacy of retiring Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, I wondered if anyone in the country other than Professor Shapiro would sigh with relief and think, “Thank God — that’s one less neo-Nazi sympathizer on the court.”

Now I do not know, and in fact do not actually believe, that Shapiro responded to the news in that way. But to my mind one of Justice Stevens’s best dissenting opinions is the one that showed him open to Looney’s case for Oxford as Shakespeare, and Shapiro’s clear aim in the chapter of Contested Will entitled “Oxford” is to stigmatize Looney’s world view and that of anyone who accepts his hypothesis as “dead set against the forces of democracy and modernity,” as holders of a “retrograde vision” that “comes too close for comfort to Freud’s account of the Nazi rise to power in 1933.” For Shapiro, this world view or vision necessarily includes questionable attitudes toward Jews that he suggests Looney held.

Niederkorn is of course right to point out that this kind of thing cheapens the authorship debate because it is an ad hominem attack. It provides an example of the logical fallacies that English teachers point out to students in freshman writing classes. But there is actually more at issue here. Shapiro distorts not only Looney’s arguments but also Shakespeare’s work because of his faith in the Stratford cult. Let me explain.

Shapiro decided to write this book because — when he went on a tour to sell his last book, A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599 (2005) — he ran into many people who doubted that Will Shakspere of Stratford wrote the plays and poems of Shakespeare. At least, that is what he said in the promotional material in the back of the paperback edition of that book. But he was quick to point out that he did not plan to join the debate. It is somehow refreshing to have a university professor frankly and publicly announce that he is going to research and write a book on a subject about which he has a completely closed mind:

It’s an exasperating question, for the evidence is overwhelmingly conclusive that only William Shakespeare of Stratford could have written these plays and poems. I gradually came to understand that at the heart of this “authorship controversy” was a different set of questions with which I had not yet adequately wrestled: When and why did people start doubting Shakespeare’s authorship? Why has this been a mostly American phenomenon? What does it reveal about notions of genius, evidence, and the allure of conspiracy theories? And why have such notable figures as Sigmund Freud, Charlie Chaplin, Malcolm X, and Mark Twain subscribed to this myth? (Harper Perennial pap. ed. 2006, P.S. pp. 12–13.)

It is characteristic of Professor Shapiro that it is not enough to say there is sufficient evidence to justify thinking Will of Stratford wrote the Shakespearean plays and poems. He feels compelled to insist that “only [he] could have written” them. This is a difficult position to maintain when you also wish to insist that parts of some plays were written by John Fletcher.

Blindness to this kind of inconsistency is a sign that we are dealing here with a statement of faith rather than an application of reason to a merely human, mortal problem.

Editorial Note: Shapiro’s claim that it’s “a mostly American phenomenon” is followed almost immediately by his own list of four leading doubters — one (Chaplin) a Briton and another (Freud) an Austrian. So Shapiro cannot claim any excuse of ignorance (in 2006) about the history of the authorship question, though doubtless he may have reconsidered this laughably erroneous assertion by the time he spent 48 pages (153–200) of his 2010 book discussing Freud plus various Britons, including Looney, the quintessentially English schoolmaster who launched the modern Oxfordian theory. Shapiro’s 69-page section on the Baconian theory (pp. 81–149) emphasizes Americans, including Delia Bacon (no relation to Sir Francis), the co-founder of that theory. But the Baconian theory was also independently originated by a Briton, William Henry Smith, though Shapiro gives him short shrift (pp. 105–06).

Authorship doubts were embraced during the 19th century by countless Britons, including the prominent judge and privy council member Sir James P. Wilde, Lord (First Baron) Penzance (1816–99), and one of the most important British leaders of that era: Henry John Temple, Lord (Third Viscount) Palmerston (1784–1865), who served twice as Prime Minister of the U.K. (1855–58 and 1859–65).

Among other leading authorship candidacies, that of William Stanley (Earl of Derby) was originated by a British antiquarian in 1891 and most prominently promoted (1918–19) by one of the leading French literary scholars of his time, Professor Abel Lefranc. That of Roger Manners (Earl of Rutland) was originated by several German writers (c. 1906) and developed by the Belgian Célestin Demblon (1912) and the Russian emigré Pyotr Porohovshikov (1940).

But never mind: Shapiro says it’s “a mostly American phenomenon” and surely we can trust him. He’s a Shakespeare “expert,” right?

The most impressive authorship-doubting scholar up to 1920 — for that very reason, studiously ignored by Stratfordians for the most part — was the quintessentially English barrister and politician Sir George Greenwood (1850–1928; Liberal Member of Parliament, 1906–15), who remained rigorously agnostic about the true identity of “Shakespeare.” Shapiro’s 2010 book makes only a few brief and scattered references to Greenwood, never engaging the substance of his work. He is ignored entirely in the leading Stratfordian manifesto published to date, Shakespeare Beyond Doubt (Edmondson & Wells eds. 2013), to which Shapiro contributed a 5-page afterword.

In Contested Will itself, Shapiro doesn’t refer to his 2005 book tour, unless that is what he means when he writes of “audience members at popular lectures” (p. 6). Instead he tells the story of a fourth-grader who asked him a question after he talked to an elementary school class about Shakespeare. The boy, described by Shapiro as quiet, raised his hand and said (p. 5), “My brother told me that Shakespeare really didn’t write Romeo and Juliet. Is that true?” It’s as if this small boy’s words made Shapiro realize just how widespread the doubts about Shakespeare’s identity had become and moved him to write his book.

An odd thing about this story is that, through it, Shapiro provides himself with a motive for taking up the authorship question that is similar to the one that launched Looney on his search for the identity of Shakespeare. Looney became more and more convinced that the life of the Stratford man as we know it from the records and documents does not reflect the life of the author of the plays and poems. As a teacher, Looney found it increasingly difficult to present to students as facts statements that he did not himself any longer think were true. Almost a century later, Shapiro implies that he felt moved to rush to the defense of schoolchildren and protect them from the myths of the people he describes as “rejecters of Shakespeare.”

Editorial Note: On Shapiro’s attitude toward students who dare to express authorship doubts, see this essay, specifically the section “A Milder Form of Bullying?” See also the section on “The Outrageous Comparison to Holocaust Denial.”

Shapiro’s faith in the Stratford cult forces him to deny that there is an authorship problem. One sign of this is his ridiculous use of the subtitle: “Who Wrote Shakespeare?”

This question has all the intellectual value of the old joke that asks: “Who’s buried in Grant’s tomb?” The only legitimate way to answer the question posed by Shapiro is to imitate the voice of W.C. Fields and pronounce the Stratfordian party line: “Another man of the same name.” Of course Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare. We all agree with that. The question is, who WAS Shakespeare?

Another logical fallacy, of which Shapiro is frequently guilty, is what is known in freshman writing classes as “either/or thinking.” And this is one of the ways in which he is very different from Looney. For instance, Shapiro gives the impression that Shakespeare wrote plays either as dramatic performances or as books to be read. He himself clearly prefers performances — either live performances or movies. He admits to becoming bored in high school by teachers taking classes through close readings of the texts. For a time, he thought he disliked if not actually hated Shakespeare’s plays.

On the other hand, he later fell in love with Shakespeare’s work when he was able to see the plays on stage, especially in London. It follows from this that the idea of Shakespeare as a man of the theatre appeals to him, and he writes with obvious pleasure about Shakespeare’s role as an actor, playwright, and shareholder in the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. It also follows from this that the idea of Shakespeare as a man who wrote entertainments for pay appeals to him. Why should he have wished to do anything more or even different?

Fair enough. But Looney argues that the kind of man Shapiro pictures could not have written the plays of Shakespeare. Instead, he thinks Edward de Vere (Earl of Oxford), using the pen name “Shakespeare,” wrote plays for performance, plays that would divert the court or those who paid to see them in a theatre. But he also rewrote and reworked them so they would satisfy those who wished to linger over them longer on the printed page. And in this way, Shakespeare would achieve two purposes the ancient world assigned to literature — to both delight and enlighten his readers.

Of course it would be a good thing if performances of the plays generated money. Oxford certainly needed it. But as Shapiro points out, while publication of the plays might establish in the public mind the name “William Shakespeare,” the author would not directly derive any income from those publications. The copyrights, as it were (it’s misleading to think of “copyright” as the term is now used), would belong to the Chamberlain’s Men, not the author, whoever he was. The motive for reworking and rewriting plays so they become not only the pastime of a couple of hours, but lasting literature, would not be money. This motive is related to the question of the author’s audience.

Shapiro gives the impression that Shakespeare must have written either for his contemporaries or for posterity. For all his pseudo-learned labeling of Shakespeare as an “early modern writer,” Shapiro seems to give exceedingly little thought to the influence of the development and spread of printing on writers of the time.

Plays performed at public theatres had the ability to influence the thought and behavior of an audience that included illiterates as well as the learned. Shakespeare clearly wrote for his contemporaries who made up this audience and would wish to have something for all of them in his plays.

On the other hand, Shakespeare was aware that the writers of the ancient world spoke to him despite the fact that they were without the aid of the power of the press to make lasting works that could reach posterity. As a result, because of the press’s ability to make multiple identical copies of a text, increasing the likelihood that his own voice might reach readers in the future, he also wrote for them. He said as much: “Not monuments, nor the gilded palaces / Of princes shall outlive this powerful rhyme.”

Shapiro gives the impression that Shakespeare must have written his sonnets either as autobiography (a very un-“early modern” thing to do, he says) or, in the words of Giles Fletcher, “only to try my humour.”

It is of course ridiculous to suggest that Shakespeare’s sonnets are autobiographical in the sense that he sat down to write his life story in them. On the other hand, it seems to me much more ridiculous to insist they are works of fiction — expressing feelings the author never felt and written to people who did not exist while assuming a mask, a persona, and not speaking in his own voice.

It is far more reasonable to think a poet might well use sonnets in much the same way Montaigne in France used the essay — writing in order to try and understand himself and his situation and to relieve his feelings. “That time of year thou may’st in me behold” does not seem to me the kind of line that was written to kick off a sonnet that had no contact with the poet’s actual life, or did not have as its primary audience the ‘thou’ being addressed.

It also does not seem reasonable to think this poem was written merely to “try [his] humour” with one eye on the possibility of selling it to Thomas Thorpe more than a decade after the fad for sonnet sequences had peaked. I also think Thorpe’s use of the words “ever-living” to describe the author means — as Looney noted in 1920 (p. 355) — that the author was dead by 1609.

It is worth pointing out that Shapiro refers to Sir Philip Sidney’s sonnet sequence, Astrophel and Stella, without taking up the question whether it is “autobiographical.” It is perhaps enough to say that Sidney apparently did not realize he was an “early modern writer” when he concluded a sonnet on how to go about writing with, ” ‘Fool,’ said my Muse to me, ‘look in thy heart and write’.”

It is also worth noting, as Peter Moore shows, that what might be called the “conspiracy of silence” concerning the identification of Stella as Lady Penelope Rich was maintained (in print) until 1691. The evidence to establish the identification was not pieced together into a persuasive argument by scholars until the mid-19th century, that is, until the time when the authorship question really began. Moore appropriately ends his piece this way: “The Stella cover-up offers remarkable parallels to what we infer concerning the Earl of Oxford and William Shakespeare. It should become the standard response to sneers about conspiracy theories.” (See “The Stella Cover-Up,” republished in Moore, The Lame Storyteller, Poor and Despised, Goldstein ed. 2009, p. 312; Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, Winter 1993, PDF here, p. 12.)

Editorial Note: Indeed, as Moore pointed out in the article Hope cites, it was not until Hoyt Hudson’s definitive 1935 article that modern “scholarly” literary circles finally accepted the truth about the Stella connection, a fact probably well-known and gossiped about in Elizabethan literary circles of the 1590s. This is a telling indication, as Hope suggests, of how long such a literary “conspiracy” (of silence, at least in print) may be maintained — or at least how long academics may persist in their determination to bury their heads in the sand and avoid facing reality.

Sidney’s sonnet sequence was not published until after his death. His sonnets had circulated in manuscript until then, a practice that separated Sidney, the knight and courtier, from poets who published their sonnets in their lifetimes. This practice also connected Elizabethan court poets with those of the reign of Henry VIII, especially Wyatt and Surrey, the first English sonneteers, and translators or adapters of Petrarch.

Shapiro’s passage on the sonnets also raises the question of the censoring of the press in Shakespeare’s time. Shapiro says Giles Fletcher took to writing sonnets for a practical, political reason: “Fletcher had hoped to write a history of Elizabeth’s reign, but shelved plans for that after Lord Burghley refused to approve such a politically sensitive project.”

Shapiro, of course, does not pause here to point out that the statesman engaging in this quasi-official censorship — “Hark, a word in your ear!” (Troilus and Cressida, act 5, sc. 2) — was Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley, the father-in-law of Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Burghley has long been viewed as a model for Polonius in Hamlet by Stratfordians, Oxfordians, and others. Shapiro is, of course, opposed to identifying actual people as models for fictional characters in plays — “early modern writers” just didn’t do such things and we only think they might have done so because modern writers do and we are used to reading modern writers.

Hooey. It is almost as important to remember the tendency of human nature to stay fundamentally the same as it is to be aware that the sameness expresses itself in vastly different ways in different times and places.

Printing permitted writers to deal with potential censors by the use of pen names. If the identity of “Stella” provides one parallel with the authorship question, the scholarship that has tried to determine the identity of “Martin Mar-prelate” is another. The Martin Mar-prelate pamphlets first appeared at about the time Shakespeare is traditionally thought to have turned up in London and begun his career in the theatre.

While I must admit I have not kept up with the literature on the subject, I remember once being almost certain that “Martin Mar-prelate” was the pen name of John Penry, a Welsh priest who worked hard for the poor of Wales. Further reading made it seem more likely that Penry served as compositor and editor and was active in hiding the press that produced the pamphlets by moving it around the countryside and that the texts were written by another man who could stay put and had more leisure and whose wit and style matched that of the pamphlets.

In any case, the unmasking of this Elizabethan writer was still being debated in the academy in my lifetime and for all I know the debate continues to this day. If it is hard to reach consensus on who “Martin Mar-prelate” was, it is not surprising that it is difficult to reach agreement on who “Shakespeare” was. But the first step is to admit at least the possibility that the name could be a pen name.

Shapiro misrepresents Looney most when he discusses Looney on Shakespeare’s attitude toward money. He misrepresents him first by saying that Looney takes a large, general position on the relationship between money and writing, that he believes “great authors don’t write for money.” Although this was and remains a widely held view, a commonplace, I don’t recall Looney saying anything of the kind. He goes out of his way to make the point that money deserves respect as an important social convenience.

There is nothing in Looney’s “retrograde vision” that calls for a return to the barter system. But on the other hand, Looney also points out that there are times in history when too great a concern with money and its accumulation throws society out of whack, throws the time out of joint, and that Shakespeare lived in such a time.

The contempt expressed in the plays for money and those who give it too much attention is not merely an expression of aristocratic disdain but rather a recognition that its overemphasis does social harm, and prevents the efficient flow and distribution of the good things in life. Looney recognized that an excessive generosity, an overt carelessness about what others worried over and clung to, was the way to counter this social harm even if it meant others would think the spendthrift a fool. Shakespeare gives voice to this attitude (in Henry V, act 4, sc. 3) with the words, “Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost.”

The speech Looney focuses on is Polonius’s advice to Laertes (act 1, sc. 3) with its famous phrase, “Neither a borrower nor a lender be.” He picks that speech because it used to be taught with great frequency as an expression of Shakespeare’s philosophy — not the philosophy of Polonius, a character in a play, but the philosophy of Shakespeare, the poet and playwright who is world-famous and all but universally admired.

As Looney showed, Polonius’s attitude toward money was in this speech connected with individualism of a particular kind, the kind embodied in the words that high school students used to memorize: “to thine own self be true, / And … / Thou canst not then be false to any man.”

As Looney quickly showed, if you are true only to yourself, you cannot be true to anyone who disagrees with you or differs from you. In short, Looney used this speech to show that Shakespeare recognized that too great a concern for money and too great a concern for self did harm to society.

The opposite of Polonius in the play is of course Hamlet. He reflects his attitude toward money when he bitterly mutters “Thrift, thrift, Horatio” (act 1, sc. 2) as a sardonic way to tell his friend why his mother married his uncle so soon after his father’s death — using the food purchased for his father’s funeral to feed the wedding guests.

The contrast between Polonius and Hamlet on this question of the use of money is reflected in the way they would treat the players when they arrive (act 2, sc. 2). Hamlet urges Polonius to “see them well bestowed” and let them “be well used.” Polonius counters that he “will use them according to their desert” and in so saying gives Hamlet a chance to instruct Polonius and us if we are willing to learn:

God’s bodkin, man, much better! Use every man after his desert, and who shall ‘scape whipping? Use them after your own honor and dignity. The less they deserve, the more merit is in your bounty.

Shapiro is to some extent clearly put off and misled by Looney’s language. He uses words like “noble” and “ideal,” and opposes what he calls materialism. But the fact is that the materialist Karl Marx thought along lines similar to those of Looney so far as the question of Shakespeare on money is concerned.

An early biographer of Marx, Franz Mehring, says Marx did not let his sympathy for the working class prejudice him against Shakespeare’s aristocratic outlook. Marx himself used speeches from Timon of Athens to analyze, in an essay called “The Power of Money,” the social harm the misuse of money can do.

Looney did not, like Marx, call for the abolition of money. He simply wanted to see humanity take a rational approach to the use of it as an instrument of social convenience. It was the revolutionary socialist William Morris, not Looney, who pictured a Medieval Utopian future that flourished without money or machinery.

We seem to be getting far afield from the Shakespeare authorship question, but that is as it should be. As Delia Bacon first argued, the question arose because the misidentification of the author kept readers and playgoers from seeing and learning fully what is in the plays. Professor Shapiro himself provides a good example.

In A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare: 1599 (2005), Shapiro has little patience with, and in fact attacks, Edmund Spenser for his service to the Elizabethan state in Ireland. He writes (p. 70):

Where Shakespeare had purchased a house in his native Stratford, Spenser had moved into a castle on stolen Irish land. And what had it got him? It’s hard not to conclude that for Shakespeare, Spenser had built on sand. Premature interment at Chaucer’s feet was poor compensation for so badly misreading history. Spenser had rewritten the course of English epic and pastoral. Shakespeare would soon enough take a turn at rewriting each in Henry the Fifth and As You Like It — and would have appreciated the vote of confidence in an anonymous university play staged later this year in which a character announces: “Let this duncified world esteem of Spenser and Chaucer, I’ll worship sweet Mr. Shakespeare.”

It is not just that Shapiro here provides evidence that Shakespeare “worship” did not start in the 18th century and usher in a history of error of which the authorship question is a part. Shapiro also establishes a false opposition between Spenser and Shakespeare and suggests we must choose one or the other. He is well aware that Shakespeare paid tribute to Spenser in Sonnet 106, or at least he thought so in the bad old days when he wrote this earlier book and still thought “early modern writers” might express real emotions about real people. But Shapiro also insisted (2005, p. 70): “Spenser … had chosen paths Shakespeare had rejected. [Spenser] had pursued his poetic fortune exclusively through aristocratic — even royal — patronage ….”

Shapiro’s Shakespeare is the opposite of Looney’s — anti-aristocratic, anti-feudal, untainted by Catholicism, and able to avoid the yoke of patronage and flourish thanks to the capitalism that is breaking up the old establishment and offering opportunities to a clever, energetic man with a grammar school education who becomes an entrepreneur in a new but rapidly growing entertainment business.

In Looney’s time, people worried about misreading history for fear the human race would be doomed to repeat it. In our time, misreading history might lead an individual to miss a career opportunity. It is Shapiro’s self-identification with his Shakespeare that causes him to misrepresent Looney to such an extent that it almost constitutes character assassination.

Shapiro says Looney suggests that Shylock was based on or modeled on William Shakspere of Stratford. I must say I have no recollection of any such suggestion, and when I briefly tried to find it I couldn’t. That doesn’t mean it isn’t there. (See Editorial Endnote on this issue.) Whenever I re-read Looney I tend to be surprised at things that are there that I have forgotten — although I do not think I’ve ever thought of “Shakespeare” Identified as my bible, as Shapiro insists all Oxfordians do. (I do in fact wish more Oxfordians would read it.)

But I do recall that even though my teacher and friend, Bronson Feldman, used to say he thought it likely that Oxford had been forced by circumstances to humiliate himself by borrowing money from Will Shakspere, he said and wrote that Shylock was based on Michael Lok, a merchant (Lok’s father had been Henry VIII’s mercer), who was ruined by investing in Frobisher’s voyages in search of a northwest passage to India and China.

The Queen and Burghley contributed to Lok’s ruin by refusing to pay promised amounts when the search proved futile. Lok was placed in a debtor’s cell in the Fleet and his children were forced to beg in the streets. By 1596, Lok was a merchant in Venice, trading with what was then called the Levant, and writing to Elizabeth to commend yet another chance to invest in an adventure that promised to produce fabulous riches.

Oxford was also a big loser through investments in Frobisher’s voyages. Feldman (1914–82), in his Hamlet Himself, a book I’ve recently reissued (published in 2010), finds these losses reflected in Hamlet being “but mad north-north west.” In any case, it is this, along with Looney’s view that Shakespeare combined Catholic leanings with skepticism, that leads Shapiro to take an interest in Looney’s thoughts and statements about Jews.

It is this interest that I think explains Shapiro’s devoting the first section of his chapter on Oxford to Freud. Rather than looking at Freud as an Oxfordian in the context of Looney, we are presented with Looney’s Oxfordianism in a Freudian context.

What Shapiro feels forced to try and explain is “why one of the great modern minds turned against Shakespeare” (p. 156). This clinging to the idea that viewing the name “Shakespeare” as a pen name, used by someone other than Will Shakspere, constitutes “turning against Shakespeare,” would merely be funny if it didn’t cause so much harm — especially to Professor Shapiro himself, but also to any Oxfordian who is silly enough to take his charges personally.

I feel obliged to quote the relevant passage from Contested Will at length (pp. 188–89):

Looney’s daughter, Mrs. Evelyn Bodell, reported that a few days before he died on 17 January 1944, her father confided, “My great aim in life has been to work for the religious and moral unity of mankind; and along with this, in later years, there has been my desire to see Edward de Vere established as the author of the Shakespearean plays — and the Jewish problem settled.” That last phrase can be easily misread, especially in 1944 when it was becoming clearer what horrors the Nazis had inflicted on the Jews (among the victims were four of Freud’s five sisters, who died in extermination camps). What Looney meant by this is clarified in a letter he sent to Freud in July 1938, shortly after he had fled Vienna and arrived in London. Rather than discussing the Shakespeare problem, Looney wanted to enlist Freud’s support in resolving the Jewish one. He explains that he writes as a Positivist, as a nationalist, and as someone with no quarrel with dictatorship. While highly critical of the Nazis, he is also impatient with the Jews’ refusal to abandon their racial distinctiveness and assimilate fully into the nation-states in which they lived — the ultimate source, for Looney, of their persecution. He rejects the possibility of a Jewish homeland as impractical; the only solution, from his Positivist perspective, is their “fusion,” which, sooner or later, “must come.” Looney might have added that Oxford had foreseen as much in having both Shylock and Jessica “fuse” through conversion with the dominant Venetian society by the end of The Merchant of Venice.

Looney was consistent to the end. He had begun his authorship quest decades earlier after equating Shakespeare of Stratford’s “acquisitive disposition” and habitual “petty money transactions” with Shylock’s. For Looney, the idea that a money-hungry author had written the great plays was impossible. His originality, then, was in suggesting that while Shakespeare of Stratford was portrayed in Shylock, the play’s true author, the Earl of Oxford, had painted his self-portrait in Antonio. Looney’s solution to the authorship problem, like the resolution of the play’s “Jewish problem,” and indeed, “the religious and moral unity of mankind,” was of a piece.

I regret very much that Professor Shapiro chose not to include in his text the full letter that Looney wrote to Freud in July 1938. It is a custom in this country to let the accused speak on his own behalf, after all. But in any case we can say that there is no way to be sure Looney’s mind had not been changed or at least influenced by events that occurred between July 1938 and January 1944. He wrote Freud before the Kristallnacht pogrom of November 9–10, 1938, when hundreds of Jews were killed and hundreds of synagogues destroyed.

It is also worth pointing out that whatever Looney wrote Freud in 1938, it did not seem to affect their relationship or cause Freud to change his mind about Looney’s solution to the authorship question. (Editorial Note: Shapiro concedes, p. 155, that “Freud died in September 1939, promoting Oxford’s cause to the very end.”)

More to the point, Shapiro does quote two other letters written by Looney. But he separates those from his discussion of the subject (pp. 187–89) and banishes them to his Bibliographical Essay (p. 308).

Editorial Note: The following section of Hope’s review has been slightly revised, with some added editorial notes, to more fully and clearly reflect the underlying sources. Hope, in 2010, did not have access to Looney’s 1938 letter to Freud. Shapiro’s grotesquely unfair distortion of Looney’s letters (and overall views) becomes painfully apparent in the discussion below.

Looney stated, in a letter to Eva Turner Clark dated June 10, 1939:

In the centuries that lie ahead, when the words Nazi and Hitler are remembered only with feelings of disgust and aversion and as synonyms for cruelty and bad faith, Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Tennyson [etc.] will continue to be honoured as expressions of what is most enduring and characteristic of Humanity.

It is worth pointing out that Looney made this statement months before the pact between Hitler and Stalin and the start of World War II in Europe on September 1, 1939, with the Nazi invasion of Poland. Sixteen days later the Soviets invaded Poland from the east. The next year, on April 23, 1940, the Nazis staged an official birthday celebration for William Shakespeare in Weimar. Being a Stratfordian is no guarantee of an enlightened outlook.

The second letter buried by Shapiro in his bibliographical endnotes was written by Looney in late 1939 or very early 1940, described as “recently received” by Eva Turner Clark in the February 1940 issue of the American Shakespeare Fellowship Newsletter (PDF here, p. 5). The portion Shapiro quotes (p. 308) states: “To me, however, it [the war] does not appear to be a struggle between democracy and dictatorship so much as between material force and spiritual interests.” That reflects Looney’s view that politics, like money, was a social convenience that should be treated with respect but not overemphasized.

Editorial Note: In isolation, this passage in Looney’s letter can be twisted, as Shapiro seeks to do, to suggest Looney was minimizing the Nazi dictatorship’s threat to democracy. But Looney was a very precise writer. He did not deny or even question that the war was one “between democracy and dictatorship,” nor did he suggest any lack of support for democracy. He merely wished to emphasize that for him, that was not “so much” the issue as the contrast between what he viewed as Nazi materialism, linked to malignant nationalism, as opposed to the more universal “spiritual interests” of the Western democracies.

In any event, Shapiro terminates his quotation halfway through Looney’s sentence (inserting a period with no brackets or ellipsis), and omits what immediately follows. Here is what Looney actually wrote in the 1940 letter (emphases added):

To me, however, [the war] does not appear to be a struggle between democracy and dictatorship so much as between material force and spiritual interests; between a brutal national egoism and the claims of Humanity; and as an Englishman I am proud to feel that my country stands on the side of Humanity and spiritual liberty, and alongside of France is destined to lead the way towards a recovery in Europe of a true sense of spiritual values.

This is where our interest in Shakespeare and all the greatest of the poets come in.

Amidst the darkness of the present times we shall do well therefore to make a special effort to keep alive every spark of interest in their work. More even than in normal times we need them today, however incompatible they may seem with the tragedy that overshadows us. My own work, ‘Shakespeare’ Identified, was largely the result of an attempt t this [sic; possible scanning glitch; “to do this” or “toward this”?] during the last war [i.e., World War I, 1914–18, during which Looney researched and wrote his 1920 book]: a refusal to be engulfed by an untoward environment even when suffering most poignantly from the loss of many who were dear to me.

This then is part of our share in the present day struggle: to insist even in the slaughter and distress of battle fields and bombardments by sea and air on the supremacy of the things of the human soul.

Editorial Note: Readers should recall at this point Shapiro’s claim in his main discussion (p. 188, quoted above) that Looney was “someone with no quarrel with dictatorship,” and his overall insinuations about Looney’s views (pp. 187–89). It is appropriate to review here the actual text of Looney’s 1938 letter to Freud. All these letters were fully available to Shapiro. The specific basis for Shapiro’s claim that Looney had “no quarrel with dictatorship” was apparently this statement in the 1938 letter (emphases added here): “With the idea of dictatorship, as such, Positivism has no quarrel: the particular form of government a nation adopts is its own concern.”

Shapiro concedes (p. 188) that the 1938 letter was “highly critical of the Nazis,” though he does not bother to quote Looney’s emphatic statement to Freud near the outset that he was “shocked at the inhuman treatment being meted out” to Jews, was “in sympathy with the whole of your people,” and felt “indignation at the persecution” of Freud personally and of Jews in general. As Hope notes, this was before Kristallnacht — and well before knowledge of the Holocaust.

Shapiro chooses to omit entirely what Looney wrote immediately after his comment about the abstract stance of Positivism toward “the idea … as such” of dictatorship (emphases added): that it was “a misfortune” for government to “become identified with totalitarian ideas and military dominance,” and that the “first condition” of just and rightful government was to “recognize its own subordination to moral law, and allow … full liberty of speech and press limited only as regards direct incitement to sedition, law-breaking, or revolutionary violence. It is upon such an arrangement that the true liberties of a people rest; and the disastrous violation of the principle in modern Europe is a much graver menace than the mere subversion of democratic institutions. Moreover in a democratic state there is no guarantee of spiritual liberty.”

Thus did Shapiro twist Looney’s enlightened recognition that even democracy can threaten liberty into some vaguely implied fascistic sympathy “with dictatorship.” As Looney doubtless recalled vividly in 1938, Hitler rose to power in 1933 through democratic elections.

In the end, no matter what Looney’s opinions were, those who share his view on the identity of Shakespeare do not necessarily hold and should not be held responsible for his opinions on other subjects.

But to smear all Oxfordians indiscriminately is precisely Shapiro’s aim. He writes (p. 182):

Looney’s Oxfordianism was a package deal. You couldn’t easily accept the candidate but reject his method. You also had to accept a portrait of the artist concocted largely of fantasy and projection, one wildly at odds with the facts of Edward de Vere’s life. Looney had concluded that the story of the plays’ authorship and the feudal, antidemocratic, and deeply authoritarian values of those plays were inseparable; to accept his solution to the authorship controversy meant subscribing to this troubling assumption as well.

This attempt to smear all Oxfordians and those who might take up the position in the future is what Shapiro uses instead of a rational refutation of a rational case. A key to the approach is his reliance for the facts of Oxford’s life on Alan Nelson’s Monstrous Adversary (2003).

Shapiro says Nelson’s description of Oxford’s life is harsh and authoritative, which must be Stratfordian for malicious and untrustworthy. (Editorial Note: See “Nelson, Monstrous Adversary: Five Reviews.”) It is now clear that Shapiro and Nelson, the good cop-bad cop of academic Shakespearean studies, represent a new phase in the history of the authorship controversy. First silence, then ridicule, and now attack — the academic Stratfordians have exhausted the three main ways that people in power use to respond to threatening ideas. What should we expect from them next?

Shapiro has already announced his next book, The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606, a title that brings up another way he misrepresents Looney’s work. (Editorial Note: Shapiro published Year of Lear in 2015, debunked by an Oxfordian rebuttal in 2016.)

Shapiro writes in Contested Will (pp. 178–79):

The greatest challenge Looney had to meet was the problem of Oxford’s death in 1604, since so many of Shakespeare’s great Jacobean plays were not yet written, including Macbeth, King Lear, Coriolanus, Antony and Cleopatra, Timon of Athens, Pericles, The Winter’s Tale, Cymbeline, and Henry the Eighth. Looney concluded that these plays were written before Oxford died (and posthumously released one by one to the play-going public) or left incomplete and touched up by lesser writers (which explains why they contain allusions to sources or events that took place after Oxford had died). [Editorial Note: They don’t. See “Authorship 101,” FAQ #4.] It was a canny two-part strategy, one that could refute almost any counterclaim.

The last sentence offers another reason for Shapiro’s complete misunderstanding of Looney’s work and character. Looney was neither a professor with a strategy for shaking grants and fellowships from the academic plum tree, nor a faculty advisor to a debating team who wished to train students to win arguments whether they believed what they were saying or not. He was making a serious effort to understand questions that had made a chaos of the study of Shakespeare, a chaos that continues to this day and supports armies of academics.

Professor Shapiro states as a fact that these plays were written after Oxford’s death, merely because his adherence to the Stratford cult means that he must follow the chronology of the plays established by Sir Edmund K. Chambers, or some variation that results from more recent tinkering, largely intended to keep the dates away from Oxford’s lifetime.

Looney, alas, was not given this revealed truth and so had to stumble along in the dark — relying on the authorities who had tackled the subject up to his own time and on his own exceedingly good common sense and honesty. Based on subject matter, versification, and a sense of the playwright’s development, Looney argued that a number of these so-called late plays had much more in common with early ones than with those that were certainly late. The Winter’s Tale and Pericles, for instance, seem more at home living in the vicinity of A Midsummer Night’s Dream rather than taking up residence next door to Macbeth’s bloody castle.

No less an authority than the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge had proposed a similar grouping of the plays, as Shapiro knows because he reports it in his book. Coleridge’s view does not mean much to Shapiro, though, because he was only a poet, not a professional Shakespeare scholar.

Before Shapiro rushes into print a book insisting that King Lear was written in 1606, I hope he will read Bronson Feldman’s evidence showing that Robert Armin, the clown who is thought to have played Lear’s fool, was a servant of the Earl of Oxford. Armin’s written work states that he served a Lord in Hackney and Feldman argued, persuasively to my mind (though reasonable people may certainly disagree), that the only Lord then living in Hackney who had connections with the theatre was Oxford.

Editorial Note: Shapiro published Year of Lear in 2015, debunked by an Oxfordian rebuttal in 2016. He discusses Armin only briefly in Year of Lear (pp. 27–28, 183), not in any way suggesting he read Feldman. Since, as in Contested Will, Shapiro fails to provide in Year of Lear any alphabetical listing of scholars upon whose works he relies, instead merely a “Bibliographical Essay” (pp. 311–51) citing sources in the order he happens to rely upon them, we invite anyone to alert us if any citation to Feldman is buried in that 40-page haystack. We doubt it, and haven’t yet found one.

Shapiro, in his 2005 book on Shakespeare in 1599, is good on the shift in the Lord Chamberlain’s Men that took place when William Kempe, the dancer and comedian, left the company and was replaced by Robert Armin. He there shows how this shift in personnel was reflected in a shift in Shakespeare’s comic roles. He convincingly argues that the author of the plays had to be familiar with these actors’ strengths and weaknesses in order to write parts that would make the most of their talents. If I’m not mistaken, Nelson in Monstrous Adversary showed that when Kempe was a servant of the Earl of Leicester, he crossed paths with Oxford in Holland.

Armin, after joining the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, served a Lord in Hackney, living at King’s Place. If Professor Shapiro gives himself a chance, he might come to imagine that those visits of the clown to King’s Place, to divert his master when drawing closer to death, might make a more likely source for the relationship between Lear and his fool than anything going on in 1606. By the way, Lear’s allowing the fool to enter the hut and escape the storm before he, a king, did, shows what Looney meant by the feudal ideal — the strong and powerful feeling duty bound to protect the weak and helpless.

Stratfordians refuse to consider this kind of thing — Feldman first published his evidence in 1947 in the American Shakespeare Fellowship Quarterly for autumn of that year (PDF here, p. 39) — because they mix it up with another quibble over names. I hate to think how much ink has been spilt and energy expended to try to show either that Oxford as “Great Lord Chamberlain” could not have been the patron of the Lord Chamberlain’s players or that because various other courtiers held the title “Lord Chamberlain” it was impossible for Oxford to have had any role or influence in it.

If Burghley could keep a man from writing a book with a word, Oxford and his friends could easily have arranged for Oxford to write for and work with the players whether they wore his livery or that of one of his fellow courtiers and friends. It is in this company or cry of players, which included both Robert Armin and William Shakspere and maintained its links with their Lord in Hackney, that we can start to understand the ground which might lead to a resolution of the authorship problem.

William Shakspere could buy New Place in Stratford in 1597 and go back and forth from Stratford to London while working in the theatre and Edward de Vere, Earl of Oxford, could reside at King’s Place and write and revise plays and work with the players in much the same way that Hamlet does.

But for work to progress in that direction, it will be necessary to stop treating the authorship question as a religious quarrel that demonizes those with differing views, and admit that we are all ignorant and will die that way despite our best efforts, but if we work together while on this whirling mud ball, moving through infinite space, we just might leave the next generation a little less ignorant than we are.

To my mind, the hero of Shapiro’s book is that fourth-grader (p. 5), who can serve as a model of scholarship: “My brother told me that Shakespeare really didn’t write Romeo and Juliet. Is that true?” He cited his source, quoted him fully and accurately, and then asked the most relevant question he could think of.

Professor Shapiro doesn’t tell us how he responded to the boy and that might be just as well. But if he goes ahead with his Year of Lear: 1606, I hope he’ll have the good fortune to run into a kid who will raise his hand and say, “My brother told me William Shakespeare died in 1604 and you believe he wrote a play in 1606. Is that true?” (Editorial Note: As previously noted, Shapiro published Year of Lear in 2015, debunked by an Oxfordian rebuttal in 2016.)

Editorial Endnote:

Hope correctly questions Shapiro’s suggestion that (as Hope puts it in the review above): “Looney suggests that Shylock was based on or modeled on William Shakspere of Stratford.” Hope did not recall any such suggestion by Looney, but conceded he may have missed it. Looney’s book in fact never directly links Shylock and Shakspere, nor does he suggest that the author “Shakespeare” (Oxford) “based” Shylock on him. The closest Looney comes to such a suggestion (Warren ed. 2018, p. 98) is a comparison of the author with Antonio, “the hero of [The Merchant of Venice]” in Looney’s view. He notes that Antonio is overly generous in lending money gratis, in contrast with “the money-grubbing Shylock.”

But Shapiro’s treatment, though tendentious, is not without some basis. Looney arguably implies a Shakspere-Shylock comparison by drawing a contrast (p. 98) with “what is known of the man William Shakspere.” Looney comments: “It ought not to surprise us if the author himself turned out to be one who had felt the grip of the money-lender, rather than a man like the Stratford Shakspere, who, after he had himself become prosperous, prosecuted others for the recovery of petty sums.”

Shapiro’s first reference to this (p. 171) captures it fairly enough: “Looney wondered …. Surely the play’s author more closely resembled Antonio than Shylock ….” Returning to the issue a few pages later, however (p. 188), in a passage quoted in full in Hope’s review, Shapiro claims (more loosely and bluntly) that “Looney … equat[ed] [Shakspere’s] ‘acquisitive disposition’ and ‘habitual money transactions’ with Shylock’s.”

As Hope explains, this is part of a tendentiously unfair passage (pp. 187–89) in which Shapiro strains to insinuate (without quite saying so) that Looney was an anti-Semite — and to smear him, by vague and remote association, with social views related to the broader context of widespread English and European anti-Semitism, which in turn contributed to the Nazi Holocaust.

Typically for Shapiro, he never seems to grasp that this insinuation about Looney (profoundly false and unfair in itself, as Hope explains) is no more relevant to the merits of the authorship question than is the actual apparent anti-Semitism of the author “Shakespeare” himself in The Merchant of Venice, reflecting attitudes horrifically pervasive in early modern European societies which foreshadowed the catastrophic genocides of the 20th century.

[published on the SOF website April 20, 2010; updated with editorial notes 2021]